By

At the end of March and into early April, when the Prime Minister and Treasurer were announcing mounting restrictions on socialising, and discussing the economic shutdown in parameters of months, not weeks, it was hard to see when an end to this pandemic could be in sight.

“We will be living with this virus for at least six months,” PM Scott Morrison warned ominously, “so social distancing measures to slow the spread of this virus must be sustainable for at least that long to protect Australian lives.”

There was no reading between the lines necessary, as ScoMo was making it very clear: we’re effectively shutting down the country for a minimum of six months, and we’re prepared to keep it closed for even longer if we have to.

Incredibly – some might even say miraculously – we’ve avoided a health crisis in Australia, with the growth in coronavirus cases nationwide slipping to a rate that is the envy of other countries.

The single-figure totals reported in relation to growth in the number of cases include many states that are recording zero new cases day after day.

As a result, the ending of this economic catastrophe could be approaching sooner than we think – or, rather than an ending, we couldsee the beginning of a new way of doing business.

Business and financial commentator Peter Switzer, founder of the Switzer Group, believes the stock market is starting to build in an expectation of the economy rebuilding, and he has his money on a return to busy offices and many corporate workers being back at their desks within a matter of weeks.

“My local coffee-shop owner in Sydney’s CBD opened up again ... after a three-week shutdown. Sue, the owner, told me that we wouldn’t be back to normal for her business for a year! The poor woman is a victim of the media and their perpetual preoccupation with worst-case scenarios,” Switzer explained in a briefing.

“I felt so sad for her. I told her that her building, usually full of coffee-addicted office workers, would be back and buying by some time in June. She loved hearing this – it gave her hope. And I think I’ll be on the money with my prediction, and world news sources are backing my big call. If I’m right, all of these woefully scary predictions about big bank losses of $35bn will be wrong.”

What makes Switzer so confident of a strong economic return? First, he points to some numbers. The Australian dollar is a proven test of market sentiment, Switzer says. On 23 March it hit a fresh low of US$0.54, and by the end of April it was back up to nearly US$0.65.

“The confidence pendulum is swinging to the positive, and only a second wave of scary infections will derail this positivity,” he says.

“If there is no significant second wave, then the scary predictions of a deep recession, 10% unemployment, a 40% collapse in house prices and banks facing $35bn worth of losses will all be BS, to put it crudely.”

At this point it’s important to remember that Australian banks are, historically, extremely profitable, so even a massive fall in profits as most of the big four have announced in recent weeks can be buffered by huge profit reserves.

Ian Pollari, head of banking, KPMG Australia

“The majors have the opportunity to use COVID-19 as a catalyst to accelerate their digital transformation, simplification and operational resilience efforts” Ian Pollari, head of banking, KPMG Australia

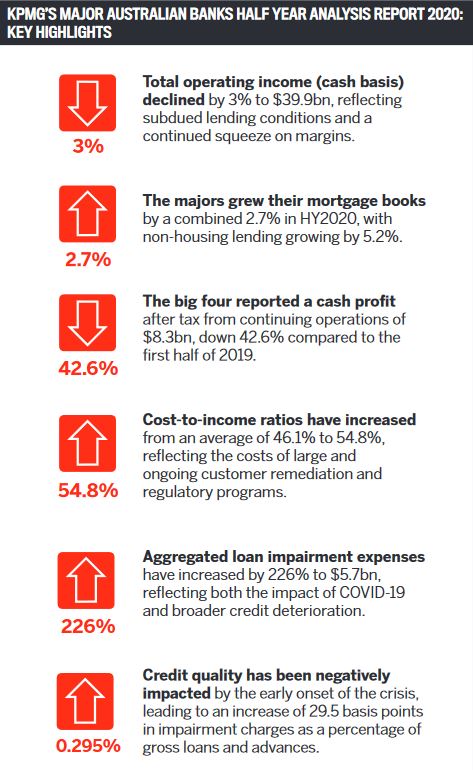

Just look at the stats: KPMG’s Major Australian Banks Half Year Analysis Report 2020 found that the majors reported a combined cash profit after tax from continuing operations of $8.3bn, down 42.6% on the same period in FY2019.

The Australian economy faces an unprecedented level of uncertainty surrounding the size and duration of the financial downturn resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, and 2020 will be a year when the majors will play “a critical role supporting the economy to withstand the impact of the crisis and to help in its recovery”, says Ian Pollari, KPMG Australia’s head of banking.

However, it’s against this backdrop of lasting profits that the major banks have recorded their recent dip in profitability.

Revenue and margin pressures continue, with elevated cost bases and deteriorating asset quality impacting negatively on industry returns. But the big four banks are facing these exceptional circumstances in a relatively strong position – from a liquidity, funding and capital perspective – compared to during the GFC.

“The biggest challenge for the major banks will be balancing the necessary support for the recovery effort and in doing so, restoring their reputations, whilst at the same time navigating a number of structural headwinds,” Pollari says.

“It is clear that the effects of this crisis will be long-term and profound in terms of impact. However, the majors have the opportunity to use COVID-19 as a catalyst to accelerate their digital transformation, simplification and operational resilience efforts.”

Hessel Verbeek, KPMG’s strategy partner, banking, added that while the major banks have proven resilient so far, it is “too early to estimate the full impact of the COVID-19 crisis” on their 2020 performance.

“The majors will have to contend with the demands of customers who want relief from loan repayments, a government which wants credit made available, a regulator which wants unquestionably strong balance sheets and shareholders who want strong profits and dividend payouts,” Verbeek said.

At the end of April, NAB revealed that it needed $3.5bn in capital to get through the next six months in particular, and that an 83 cents dividend “was going to be butchered by 64%, down to 30 cents”, Switzer points out.

“That would have shocked dividend-collecting investors and retirees who love bank dividends. But this is what happens when GFC-style crashes come along, and that’s what we’ve prepared ourselves for with this damn pandemic, which has bred lockdowns and closures of our economies,” he explains.

Furthermore, he notes that much of the forecasting and predictions being reported in recent weeks have been “Armageddon stuff ” that both the stock market and Switzer himself “don’t believe will be the reality”.

“NAB’s dividend cut is understandable, but if we continue to kick the coronavirus’s butt, our economy will recover quicker than expected and the economic and income losses of March through to June will be gradually offset by rising incomes, unbelievably low interest rates and a pipeline of government stimulus on steroids that could propel our economy into a very strong financial year from 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021,” Switzer says.

Peter Switzer, founder, Switzer Group

Peter Switzer, founder, Switzer Group

“The confidence pendulum is swinging to the positive, and only a second wave of scary infections will derail this positivity” Peter Switzer, founder, Switzer Group

“That could happen if the months of January and February keep the March quarter positive and the June quarter is the only one that ends up being a big negative. I guess if we get back to work in June, then the July–September quarter could sneak into the positive. For that to happen, we’d have to see no significant second-wave infections – and that’s a threat that the stock market is betting against right now.”

Shane Oliver, head of investment strategy and economics and chief economist at AMP Capital, has adopted a similarly optimistic view.

“Surprisingly, though, only 3% have reduced home loan payments,” he explains.

“Credit growth also surged in March, although this was all due to a surge in lending to businesses as the shutdown hit. The terms of trade rose in the March quarter, providing an income boost to the economy, and it also looks like net exports contributed positively to March quarter GDP growth.”

In addition, the ANZ-Roy Morgan Consumer Confidence Index rose for the fourth week in a row at the end of April and has now recovered nearly half of its coronavirus-related plunge.

The outlook for the economy, Oliver argues, isn’t as dire as many had predicted.

“After a strong rally from March lows, shares are vulnerable in the short term as economic data to be released over the next month shows the devastating impact of the coronavirus-related shutdowns. But on a 12-month horizon, shares are expected to see good total returns, helped by an eventual pick-up in economic activity and massive policy stimulus,” he explains.

“Provided we are right and shutdowns ease in the months ahead, resulting in April or May proving to be the low point in economic data, then given the massive policy stimulus, shares should be able to resume their rising trend and so we retain a positive 12-month outlook.”

The Australian housing market is weakening in response to the coronavirus, with social distancing driving a collapse in sales volumes, and “a sharp rise in unemployment and a stop to immigration through the shutdown posing a major threat to property prices”, Oliver says.

“Prices are expected to fall between 5% to 20%, but government support measures including wage subsidies and bank mortgage payment deferrals, together with a plunge in listings, will help limit falls at least for the next six months,” he predicts.

Shane Oliver, chief economist, AMP Capita

“This has so far turned out a lot better than feared in March, when share markets had fallen around 35% and the worry was of a much longer lock downturn” Shane Oliver, chief economist, AMP Capital

“This has so far turned out a lot better than feared in March, when share markets had fallen around 35% and the worry was of a much longer lock downturn, which would have had a far bigger impact on economic activity,” he adds.

“In Australia the official talk was of a lockdown or hibernation of at least six months. The last time Australia’s PM referred to a six-month hibernation was back on the 7th April. If the lockdown starts to ease through May as appears likely, then it will have lasted two to three months depending on when measures are completely relaxed, implying a smaller hit to the economy than originally feared.”